By Urban Puritano

•

January 6, 2026

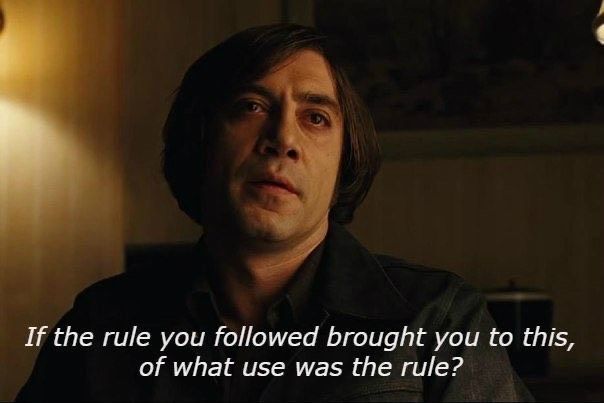

"If the rule you followed brought you to this, of what use was the rule?" Anton Chigurh "Until the four-fold method becomes critical of its own theoretical foundations and develops a hermeneutical theory adequate to the nature of the text which it is interpreting, it will remain restricted--as it deserves to be--to the romanist guild and the papist adjacent academy, where the question of truth can endlessly be deferred." (Not David Steinmetz) Introduction Some things are so fundamentally flawed, coming up with alternatives should be easy. Some things are so fundamentally flawless, coming up with refutations should be impossible. The quadriga is one such example of the former while the single sense of Scripture is an example of the latter. But times have changed and some Protestant scholars are increasingly giving Rome's official hermeneutic the right hand of fellowship. There has been too much intellectual hospitality in Protestant/Evangelical seminaries extended towards the viability of the quadriga as a model for Biblical interpretation. So much so, this medieval method is being retrieved or rehabilitated under the guise of a Christocentric hermeneutic or an Apostolic way of reading the Scriptures. This represents a dishonest downgrade for Evangelical theology in general and for Reformed confessional theology in particular. It is a woefully inadequate critical appraisal of the quadriga at best and a spiritual betrayal to be repented of at worst. A representative sample of two Reformed confessions of faith are united in confessing " the true and full sense of any scripture...is not manifold, but one ". Both the Westminster Confession of Faith and the Second London Baptist Confession of Faith use the same language to deny the manifold sense of Scripture envisaged by the quadriga and affirms Scripture's single sense repudiated by the quadriga. Soon, there will be a full court press hailing the quadriga's supposed hermeneutical virtues. What was once confined to a few lecture halls of Protestant academia will be delivered far and wide with the upcoming publication of a book endorsing the quadriga for Evangelicals. Dr. Patrick Schreiner's book on the subject will probably be endorsed by a wide cross section of academics on both sides of the Tiber. Whether it's a full throated retrieval of the quadriga or only a limited one for its integration into Protestant Biblical interpretation remains to be seen. Neither possibility is hermeneutically viable. One thing is for sure, though. The ground has been prepared for some time by some who have learned and taught its tolerance as a benign model of hermeneutics consistent with Biblical sensibilities. Much intellectual hospitality has been given to the quadriga by certain retrieval minded Evangelicals. Instead of the temporary hospitality of critical appraisal, the quadriga has moved in. What also remains to be seen is if the doctrinal deliverances of the quadriga will make their way inside. Time will tell if this has a leavening effect. Acceptance of the quadriga by Protestants, Evangelicals, and confessionally Reformed isn't viewed as that big of a deal. What is the quadriga's "Triage" score? Any alarm can be assuaged by a consideration of its long track record, right? As David Steinmetz has stated: "The medieval theory of levels of meaning in the Biblical text, with all its undoubted defects, flourished because it was true, while the modern theory of a single meaning, with all its demonstrable virtues, is false." What, then, are the Quadriga's defects that lead the Reformers and their confessional heirs to enshrine, not its embrace, but its rejection? The short answer via YouTube by yours truly: https://youtu.be/p8g9pQi2pUs?si=XwKVFvg8Y20yDyF0 The short answer via podcast: https://share.transistor.fm/s/89564a04 (The long answer will be summarized in this brief outline that comprises this blog piece. Links to the longform podcast episode at the end). Although you can't just pick up the Bible and leisurely read it like any other book, you cannot read it rightly unless you read it similarly to most other books every step of the way. After all, to read is to interpret and to interpret is to read rightly. This prompts some questions: How should a sincere believer, whether learned or unlearned proceed to read Scripture rightly? Are the quadriga's defects prohibitive rationally, Biblically, and confessionally? Some, with varying confessional commitments, like Mitchell Chase, Brandon Smith, Craig Carter, Peter Leithart, Matthew "Tossed To and Fro" Barrett, Luke Stamps and others have to a greater or lesser degree found the Quadriga to be a legitimate means to understand the written Word of God in all its polyvalence. Who can blame these academics? There is a strong tradition of interpreting Holy Writ, at least academically, in the fourfold sense. Whereas before such a method was taught and promoted among Roman Catholic academics, it is increasingly being tolerated or even touted by Evangelical academics sometimes under the guise of Christocentrism or reading the Old Testament like the Apostles did. Because of this, many young scholars and their younger seminarian whipper snapper acolytes are ignorant of the quadriga's deficiencies. This represents somewhat of a pyrrhic victory snatched from the jaws of rational, Biblical, and confessional defeat. Major Reformed stalwarts of the past like William Perkins commonly held the medieval Roman Catholic quadriga in disdain to such an extent he averred that "her device of the fourfold meaning of the Scripture must be exploded and rejected." ( Art of Prophecying ). Nowadays? Not so much. The quadriga is being massaged and repackaged without batting an eye. In a Room for Nuance interview promoting a previous work of his that dipped its toe into the quadrigan pool for interpreting the Transfiguration, Dr. Patrick Schreiner says : PS: "What I love about the Quadriga, the fourfold sense, is there's an order. You first start with that original question." Host: "So, it's not just four. You actually have to begin with one." PS: "That's what I'm kind of saying. And I do think that's what people throughout church history have said. There is actually, you begin with the literal sense. It's all based on literal sense. Then you go to the Christological, allegorical sense. Then, this is what I think is so helpful. Then you ask the question, what does it mean to me? And I love this because there's actually a gospel shape to it. Because you don't ask what it means to you until you've gotten to the gospel message of what is Christ. So, the danger in asking, what does it mean to me, is you moralize the text. You don't actually get to the gospel. But if you ask these in the right order, you actually get, oh, this applies to me as I am in Christ. As I am forgiven in Christ, then the text begins to mean something to me, because this is actually divine word, which speaks to me. We are still part of the covenant people of God. So this wasn't just written to people long ago. It was written to us because we have dual authorship here. We are the authors, the human authors and divine author." These types of remarks reflect an embrace of the medieval Catholic couplet summarizing the quadriga: "The literal sense teaches historical events, the allegorical sense teaches what to believe, the moral or tropological sense teaches what to do, and the eschatological or anagogical sense teaches our ultimate destiny." Instead of representing a continuity with classical Reformed rejection of the quadriga, these sentiments represent a discontinuity of the confessional Reformed rejection of the quadriga. What is the Quadriga? The quadriga is a medieval method of biblical interpretation crystallized in the Roman Catholic academy, whereby a dualistic bifurcation takes place. There is in Scripture a literal sense and a distinct spiritual sense. The literal sense consists of whatever meaning the words of Scripture render in ordinary ways derivable from a consideration of linguistics, philology, semantics, grammar, syntax, and historical considerations of its content. The latter spiritual sense encompasses three components distinct from the literal sense and each other, thus totaling four in all. These 3 further distinct domains of non-literal, spiritual meaning are: • Allegory or figurative signs used to signify something else • Tropology or moral lessons and imperatives • Anagogy or future focused eschatological hope These three senses encompass the spiritual meanings of Scripture statements in contrast and contra-distinction to the literal sense of Scripture. Hence, the name of this method of Biblical interpretation is the quadriga, which is a word that comes from the Latin for a chariot drawn by four horses abreast. The metaphor is apt since it is not four horses in a row one after the other, but four horses abreast or at each other's side with no one horse overtaking the other. Proponents, both medieval and modern, perceive in the quadriga interpretive virtues emerging from the polyvalence of Scripture itself. Dr. Richard Muller, for example, describes (not prescribes) how the quadriga tracks with "the character of the relationship between medieval exegesis and medieval theology, between sacra pagina and sacra theologia. The text of Scripture in its fundamental meaning is a historia salvationes, from which teaching can be drawn to address Christian faith, love, and hope. The history of the text itself in its literal meaning, together with its doctrinal implications, correspond with the four elements of the quadriga--while the quadriga or fourfold exegesis, in turn, corresponds with the fundamental needs and interests of theological formulation." ( Post-Reformation Reformed Dogmatics, V. 2, p.22 ). Muller describes it all so neat and tidy. It almost seems sinful to question the quadriga's historical development, from its earliest two senses to three senses, to its eventual final four senses. And if one goes back further to the quadriga's supposed source in Holy Writ itself, it would certainly seem even more sinful to question the contrast between the life-giving spirit and the life-killing letter as a Biblical warrant for what the Quadriga, as an interpretive paradigm, is and seeks to do. It would be quite an irony if of the many false deliverances of meaning in the quadriga's history of interpretation, the attempt to justify it from 2 Corinthians 3.6 turns out to be a stretch. Bugs or Features? What, then, are the quadriga's defects? In no particular order, let me suggest the following. First , the quadriga's conceptual clarity as a hermeneutical or exegetical resource should be critically examined . Is it best hermeneutical practice to approach Scripture assuming it will yield four distinct senses? This seems to be an unwarranted assumption on its face since exegetical interpretive processes should only seek to draw out from the text whatever sense or implications have warrant, not imposing a sense from the interpreter's pre-existing mental schema. In medieval times, the quadriga's schema was fourfold sense grid. In modern and postmodern times and methods, the schema will differ. Must the medieval quadriga reject postmodern methods or perhaps incorporate them and add more senses to the scripture? If it is axiomatic that the quadriga's fourfold sense provides best practices nowadays, why didn't the previous periods of church history with two or three senses of Scripture have staying power? Does the evolution from two to four senses of Scriptural meaning demonstrate progress in the art and science of Biblical interpretation, but such progress is no longer possible? It would seem chronological snobbery is a possibility not only towards the past, but towards the future. However, whatever number of senses one holds to for a manifold sense of Scripture, the defect in conceptual clarity remains: hermeneutics and exegesis is about drawing out textual meaning, not possessing it before the start. Second , as a consequence of the first, the quadriga seems fundamentally anti-reader . I mean this as an objective claim or reason. I know many Protestant evangelical scholars have written testimonial articles, essays, and a soon-to-be-published book on the quadriga's hermeneutical viability and virtues. Most of these testimonies are in the subjective realm. Reading homilies from the Church Fathers and being enraptured by their theological depth has opened new vistas of biblical truth for such academics and their young whippersnapper acolytes. However, not distinguishing properly between a Church Father's rhetorical skills in weaving biblical allusions to audience adaptations and applications, or worse, failing to distinguish between compositional allegorical affordances in the text of Scripture (very few, if any genuine) for interpretive allegorical imaginations from the minds of the Church Fathers (an abundant number) is a recipe for failure to read Holy Writ rightly. The reader of Scripture is better served by upholding in his mind only what can be justifiably warranted by the text of Scripture itself. Caused and composed by the Divine Author and human authors, respectively, the reader was meant to encounter and draw out meaning from all its features and compositional affordances. That's how communication works, and the Scriptures, as Divine Communication, work no differently. Communication does not work by statements with four distinct senses. As such, the quadriga is defective by being fundamentally anti-reader. Third , the quadriga is defective by militating against the perspicuity of Scripture. Not only is the issue of how man must be saved clearly read throughout Scripture, but the general tenor of the Bible is clear enough to the average person to catch. Whether learned or unlearned, the reader of Scripture can clearly discern the variety of textual terrain and what the biblical landscape displays in all its diversity of stylistic traits and its rich abstract theological features. The Bible may vary in genre and style, but the character of Scripture's content is fundamentally pro-reader by being generally clear. Scripture’s content and overarching storyline composed of myriad “stories, examples, precepts, exhortations, admonitions, and promises” (William Ames, The Marrow of Theology , 187–88) concerning God’s redemptive purpose and man’s salvation are sufficiently “clear and evident.” Both scholar and layman can by the same means arrive at the answer to how a holy and just God can bless rebellious, sinful mankind with salvation. As it was before for shepherds, warriors, royalty, and fishermen and as it continued to be for monks, maidens, lawyers, and tinkers, so the Bible’s message continues now―sufficiently “clear and evident” to all who would apply “a due use of the ordinary means” (2LBCF 1.7). How? By a due use of the ordinary means of learning. A critical and judicious use of both inductive and deductive interpretive tools can be learned at a relatively young age and confirmed and expanded upon as the believer grows in wisdom and knowledge of God's Word. The inductive analysis of Scripture afforded by comparing Scripture with Scripture, especially unclear portions with clear portions (i.e., the analogy of Scripture), takes into account the text’s diverse features without bifurcating the literal from the spiritual, the Old Testament from the New Testament, or a single passage from its canon-wide context. For this reason, most talk cautioning against atomistic reading of Scripture is misguided. At least for the confessional Calvinist since there is no dualistic distinction between the letter and the spirit, the Old Testament and the New Testament, and a single passage from its fuller meaning. After all, the deductive synthesis of Scripture afforded by the uniformity of Scriptural teaching judiciously arrived at takes into account the resulting system of doctrine emerging from the whole of Scripture (i.e., the analogy of faith), which is the confessional Reformed Christian’s “rule of faith and life.” This respects both the human and divine dimensions of the Bible. In sum, we can always delve more deeply into a text of Scripture as long as we understand a text’s meaning isn’t marooned from the rest of the canon much less assume a necessary dualism of letter and spirit in the manner the quadriga upholds its manifold sense. Remember, as we do compare Scripture with Scripture (analogy of Scripture), we accumulate biblical evidence. Implications are validly drawn out, possible interpretations are eliminated, and control beliefs are modified and subjugated to the total truth of God’s Word. Because Scripture cannot be broken (John 10:35), what emerges as texts supplement texts in a holistic, systematic fashion is a uniformity of teaching (analogy of faith). The analogy of faith cries out to us to reach for the baton of well-established and judiciously arrived-at Scriptural doctrine and continue running the race. Fourthly , the fourfold method of the quadriga has inherent problems for rational, exegetical, and logical procedures to draw out meaning. If all of Scripture is assumed to have these four particular domains of meaning, exegesis is more akin to a foregone conclusion in search of data. The fourfold method draws out meaning by putting it there to start with. In other words, exegesis is now become eisegesis. Methodologically, the fourfold approach is nothing more than transposing interlocking spiritual senses, the allegorical, tropological, and anagogical, onto the literal sense. It pays lip service to the foundational reality of actual events, persons, places, propositions, and relationships in the text of Scripture to get to the higher level, spiritualized senses. Oh yes, I know, the medieval and now some of the moderns who give the quadriga a pass are quick to distinguish, in theory, the allegoria in factus from the allegoria in dicta or verbus. But this labeling of the letter of Holy Writ and the spirit of Holy Writ is no rational help in the process of drawing out the sense of scripture. The rubber does not meet the road when the need is created for a partitive exegesis of sorts , because the dualistic bifurcation of God's word is held on to. Instead of opening up hermeneutical vistas for fruitful exegesis, the quadriga only serves to double down on dualism and bifurcation of the literal from the spiritual, when no such division exists. Remember, the spiritual sense is composed of three distinct domains of meaning, distinct from each other and the literal sense of Scripture. The correct and vital posture is to recognize and remember the following: The Bible is at once nothing more than literal and nothing less than spiritual. By way of illustration and analogy, consider the incarnation. Dr. Iain Proven is quite correct when he states, "I do not see Scripture as primarily human in nature, any more than I see Christ as primarily human in nature. I see Scripture as fully human in nature. And then also as God's word to us" ( "Become a Text Critic": The Reformation and the Right Reading of Scripture ). It is this "seriously literal" approach (as Provan calls it) of the Reformation that alone receives the revealed, inscripturated Word of God as His communicative intent meant it to be received. Moreover, when the Bible's hypostatic union of sorts isn't recognized and remembered, and instead bifurcated, such as in the case of the quadriga, interpretation inevitably results in ambivalence on any given meaning of the four senses. This ambivalence in interpretation takes the form of interpretive subjectivity. In Reformed and confessional circles, it is often snickered at and found worthy of mocking to hear of a Bible study where the teacher goes around and asks attendees what a text under consideration means to them. But the quadriga is more ambivalent to the four senses than is acknowledged and more subjective than is admitted. Especially by some Evangelical and Reformed professors and pastors who are giving it a pass as a viable option for biblical hermeneutics. St. Bernard, interestingly and unironically, presents the problem of ambivalence towards the four senses bluntly. He stated: "I know that I have explained this passage more fully, and in another sense, in my book Upon the Love of God. And if it shall please any of you to read that, he can decide whether of the two is to be preferred. A prudent person will not, I think, condemn the giving of the two senses to the same passage, provided that each appear to be grounded in the truth, and that charity, which is the rule in interpreting scripture, shall edify the more persons, inasmuch as there are a greater number of truthful senses, which each may apply to his own special need. For why should that be found faulty in the interpreting of Scripture, which we see is industriously practiced in other things? To how many different bodily uses, only to take one example, do we put the element of water? In the same way, a person is not to be blamed who gives divers senses, fitted to the various needs of souls, to a passage of Scripture." (Saint Bernard of Clairvaux's Sermons on the Song of Songs as found in Life and Works of Saint Bernard, Abbot of Clairvaux, edited by Dom John Mabillon and translated into English by Samuel J. Eales, V. 4 , 310, 1889–1896). Ironically, this quote from St. Bernard might be considered to be a gold mine for some academics seeking to give the quadriga a pass. Articles, interviews, books, and the authors of such are twisting themselves in knots bending over backwards to say that the quadriga is simply attempting to apply the literal sense. However, this just demonstrates that the quadriga is not only a potential, but an actual mine field of its basic logical defects. Hermeneutics should not conflate the sense of Scripture with the application of the sense of Scripture, should it? Confessionally Reformed Biblical interpreters should distinguish well to earn the respect to merit the verdict of teaching well . A thought experiment can be helpful to appreciate more fully what we're dealing with here in practical and logical terms. Bernard says as long as each appeared to be grounded in truth, prudence would not condemn the giving of two different senses to the same passage of Scripture. Now suppose he gave an allegoria in factus interpretation in the first case, but an allegoria in dictus or verbus in the second case. Suppose further that a different saint gives another allegorical interpretation altogether. As the allegorical senses multiply through the corridor of time, some become standard within a community. That's basically capital T tradition. But even though some allegorical senses become standard through tradition, are all the alternate senses that have accumulated over time just disposed of by the exclusion effected by the standardized interpretations? So, if you consider 20 centuries of church history, you can see within it 20 centuries of the history of biblical interpretation. Saint Bernard gives two senses of the same biblical passage, with four possible senses in all, with perhaps two types of allegory. Add to that more saints throughout church history, some more famous, some obscure. If all these saints do the same as Saint Bernard, the work of standardization is going to need some major help in arbitrating, not only multiple offerings per sense, but how many overlap and how many are united in their conclusions of the four senses of Scripture as a whole. The Magisterium has entered the chat. How else do interpretations of Scripture become authoritatively standardized? I won't make the lazy assertion that the quadriga leads to Rome. No, the quadriga is simply at home in Rome. To find it in Wittenberg, Geneva, or London is tantamount to finding Alistair Begg at a trans wedding bearing gifts. I mean, it's possible, just maximally inconsistent and weird. Truth be told, medieval tradition may also speak of the three non-literal spiritual senses of Scripture, each consisting of two additional types of meaning: open and mystical. Do the math now. T his manifold meaning model of biblical hermeneutics is more historical than veridical. Saint Bernard hints at another feature, not bug, in the quadriga's nature as a hermeneutic. On the heels of its ambivalence, in the form of subjectivity, is its utilitarian or pragmatic motivation or criteria. Again, certain evangelical and reformed voices, giving the quadriga a pass nowadays, often decry the Church's downgrade into pragmatism in ministry. But the same eyes that see this problem among broader evangelicals are blind to it in the quadriga as an interpretive method. I repeat St. Bernard, quote, "A person is not to be blamed who gives divers senses, fitted to the various needs of souls, to a passage of Scripture." This pragmatism in hermeneutics puts the applicational cart before the four horses. Bernard's pragmatic and utilitarian criteria for interpretive viability has had a long history. Over seven centuries before, Gregory of Nyssa argued: "Therefore, if indeed the literal meaning, understood as it is spoken, should offer some benefit, we will have readily at hand what we need to make the object of our attention. But, if something that is said in a hidden fashion, with certain allegories and enigmas, should yield nothing of benefit according to the readily apparent sense, we will turn such words as these over and over in our mind. This is just how the Logos that teaches us in Proverbs has instructed us to understand what is said as either a parable, or a dark saying, or a word of the wise, or as one of the enigmas. (Proverbs 1:6). When it comes to the insightful reading of such passages, that comes via the elevated sense, that is, the anagogical sense, we shall not beg to differ at all about its name, whether one wishes to call it tropologia, allegoria, or anything else, but only about whether it contains meanings that are beneficial." (from introductory section in Homilies on the Song of Songs where Gregory sketches his hermeneutical approach). Because of this, perhaps, in addition to the four senses, another sense should be added: the beneficial sense . Thomas Aquinas was no dumb ox when he famously taught that if the Scripture at the literal level speaks expressly of future glory, then the Scripture passage is only to be interpreted on the literal level. Bonaventure similarly said that if the literal level speaks of faith or of love, then a higher symbolic spiritual or typological sense needn't be sought further. Nicholas of Lyra said that it was useless to seek beyond the letter of Psalm 67 for a second sense because the literal sense of the psalm is already spiritual. So much for the superficial and incorrect interpretation of the letter of Scripture killing. Hermeneutically, not only does the letter not kill, but the letter is all we've got. Remember, the letter is the work of God's causation, just as much as the things recorded by it. No need to introduce manifold meaning of Scripture by the dualistic bifurcation of the literal and spiritual senses of Scripture. Lastly , under the fourth rubric of the Quadriga's inherent defects for rational exegetical procedures to draw out the Scripture's meaning , we note its ultimately arbitrary and capricious nature. What do I mean? Arbitrariness is the quality of willy-nillyness. Any such willy-nillyness can't long pretend to have a consistent rhyme or reason, much less a restraint of use in implementation other than the pragmatically beneficial. Capriciousness is the quality of a propensity to change as unpredictably as a Mexican girlfriend mad at her boyfriend. Any such capriciousness doesn't even try to pretend to have any rhyme or reason, much less restraint for its attitude and behavior. How can this be said concerning the quadriga? Shouldn't I be more respectful of this historical, pre-critical method of biblical interpretation, being given a pass, and even being rehabilitated and retrieved by erudite evangelicals in our day? Let that sink in. When you do, you will have to answer to whether your sensibilities and interpretive practices should be guided by any respect whatsoever for this pre-modern fourfold sense grid. If biblical interpretation must yield a fourfold sense of Scripture, why four ? This is arbitrary. If biblical interpretation must not always yield a fourfold sense of Scripture, why not ? This is capricious. Talk about Latina girlfriend vibes! How you feel about dating or a hermeneutical method, however, matters very little. The quadriga shouldn't even be friend-zoned. It should definitely be broken up with if she tempted you to give her a chance and just consider her manifold sense as applications of the literal sense of Scripture. After all, the same arbitrary and capricious nature for the quadriga's fourfold sense certainly obtains for revisioning her as a model for application. No method of biblical interpretation that is either capricious or arbitrary is rationally viable. The quadriga disqualifies herself as being a rationally viable hermeneutical method by being both capricious and arbitrary. The confessional reformed interpreter, on the other hand, by rejecting the quadriga's manifold sense of Scripture, experiences no downgrade in hermeneutics by adherence to the single sense of Scripture. This sense is ipso facto rational with no arbitrariness or capriciousness. This leads to the fifth of the quadriga's defects. It contradicts our Lord and Savior Himself as He states, "The words that I have spoken to you are spirit and life." (John 6:63). Moreover, he quotes Deuteronomy saying, "Man shall not live by bread alone, but by every word that proceeds from the mouth of God." (Matthew 4:4). Every word of Scripture is spiritual and life-giving sustenance. It's meaning is ipso facto beneficent with no dualistic bifurcation. Therefore, any dualistic interpretive framework, such as the quadriga, is a failure. Such dualism only serves to subvert and subordinate the objective letter to the arbitrary and capricious spirit, if such an interpretation is subjectively and pragmatically beneficial. Ultimately, this method lacks true virtue and is unworthy of respect because it contradicts the Lord Jesus himself. The words of Christ in all of Scripture are at once nothing more than literal and nothing less than spiritual. This leads to the sixth and final reason the quadriga is hermeneutically defective. The manifold sense of Scripture as an axiomatic framework shows itself to be an unstable and uncertain starting point for rational thought and speech. This medieval model of multiplicity of meaning front loads the Scripture with communication problems that simply aren't present in the text. Scripture never asks us to choose between the literal or spiritual. It never asks us to choose between a beneficial or non-beneficial use. It never asks us to be methodologically ambivalent. Much less does the Scripture ask us to access its meaning through arbitrary and capricious senses or applications. These outcomes happen because the quadriga guarantees them from the start. Therefore, it is not merely that the quadriga has a history of bad users. It is that the quadriga itself is a bad method. The real miracle found in looking at the history of the church's interpretation of Scripture as the quadriga was being developed and employed is that there was any truth delivered at all. I suppose even broken clocks can be correct twice a day. How then can communication via rational thought and speech be maintained? Only through the axiom of a single sense of Scripture. Only such a model or framework reflects and preserves the God-breathed, rational revelation of Holy Scripture. God saying something, anything, is simply Him communicating his thoughts propositionally. And while not all of Scripture's sentences are declarative, they are rightly understood to be the equivalent. Whether Scriptural words and thoughts are expressed properly or figuratively, their sense is singular. For all the aforementioned reasons, if the Scripture yields the quadriga's manifold sense, it can have no sure meaning. Such is the communicative intent of Scripture, and it does not return void. Interestingly, the framers and signers of the Westminster Confession of Faith and the Second London Baptist Confession of Faith took the single sense of Scripture for granted against the medieval quadriga and anything like it. They weighed the manifold sense and found it wanting. Not simply its many infamous abuses and supposed ascent into spiritual biblical interpretation, but the principle of manifold meaning itself. The quadriga as an interpretive method was in and of itself seen as irredeemable. As far as they were concerned, to be deep in the history of biblical interpretation was to cease to be quadrigal. Ultimately, it makes perfect sense (no pun intended) the single sense of Scripture holds confessional status for the truly Reformed. The Westminster Confession of Faith and Second London Baptist Confession of Faith, Chapter 1, Section 9, states, "The infallible rule of Scripture is Scripture itself. And, therefore, when there is a question about the true and full sense of any Scripture, which is not manifold, but one, it must be searched and known by other places that speak more clearly." Note that in describing the discovery of the sense of Scripture by means of Scripture itself, the Westminster Confession and the 2nd London Baptist Confession of Faith also affirm and deny certain things about the meaning or sense of Scripture. To the respective questions about whether any particular passage has multiple meanings, and whether any particular passage has only one meaning, the confessional answers are explicitly to the point. Namely: 1.) No, the true sense of Scripture is not manifold . And, 2.) Yes, the true and full sense of any scripture is one . The sense or meaning of Scripture can be enhanced in such a way that one can arrive at a fuller comprehension of a text under consideration with the help of other texts of Scripture. This fuller understanding, however, has been ambiguously described as levels of meaning or applications of the meaning of Scripture by those wanting to integrate the quadriga into evangelical and even reformed hermeneutics. However, this hermeneutical movement is simply incompatible with reformed confessional statements such as found in the Westminster Confession and the Second London Baptist Confession. As previously stated, however, the same defects for the quadriga as a manifold sense model of meaning obtain for the quadriga as a manifold application model. Those professing to hold to this confessional statement cannot rationally, historically, biblically, or honestly give the quadriga a pass. The Reformed denial of the manifold sense of Scripture is also irreconcilable with the quadriga's fourfold sense reimagining as spiritual senses collapsing to the literal sense. Even this twofold bifurcation of the literal from the spiritual senses collides with the explicit confessional statement that the sense of Scripture is one. It is noteworthy that this reimagining doesn't argue that the literal sense should be based on the allegorical, tropological, or anagogical meaning. This direction and priority of the literal sense is in itself a tacit admission. To ground the spiritual senses by the literal sense and not the other way around hints at an argument for the confessional single-sense theory of Scriptural meaning. Namely, all true meaning of scripture is derived from the literal sense. Any allegorical, symbolic, figural, typological, moral, or eschatological meaning of Scripture, if true, is derived from the literal sense. The sense of Scripture, therefore, 1), is not manifold, but one, and 2), the literal sense and no other constitute the singular and true sense of Scripture. Despite its attempted rehabilitation in academia and its friend-zoning by undiscerning pastors and certain types of podcasters, the quadriga should find little appeal to serious readers of Scripture, especially of the confessional variety. As William Whitaker successfully argued, "For although the words may be applied and accommodated tropologically, allegorically, or anagogically, or any other way, yet there are not therefore various senses, various interpretations, and explanations of Scripture. But there is but one sense, and that the literal, which may be variously accommodated, and from which various things may be collected." This encapsulates the superiority of the confessional reformed biblical hermeneutic over the fallacious medieval, pre-modern quadriga. The import of Whitaker's argument and conclusion is not grasped if one doesn't realize this necessarily excludes the quadriga in principle. At an irreducible and foundational level, the pre-critical quadriga must be refuted and allowed to collapse under the weight of its own irrationality and unbiblical dualism. The confessional Calvinist must be committed to a single-sense theory, not only as a matter of historical confessional precedent, but ultimately because the Scripture doesn't endorse a fourfold sense of Scripture or anything like it. When it comes to the Bible then, the literal sense is the spiritual sense and vice versa. We've been outlining so far its foggy conceptual clarity as a hermeneutic, its methodological question-begging eisegesis, its ambivalence between the four senses in the form of subjectivity. Contemporary evangelical and reformed professors and pastors giving the quadriga a pass haven't been Berean. They haven't tested its hermeneutical spirit. They haven't looked into its DNA. They should have, but they didn't. What Would Tyndale Do? From William Whitaker, let's turn our attention to another William. William Tyndale was an outlaw. His crime? Translating the Scriptures into English, so that all would have access to God's Word. His motto might as well have been, "If translating the Bible is wrong, I don't want to be right." All subsequent quotations may be found here . (H/T: @TyndaleTweeteth on X). Perhaps, pointedly, in contradistinction to Richard Muller, William Tyndale does not consider the quadriga's manifold sense to correspond with the fundamental needs and interests of theological formulation. According to Tyndale, the Roman Magisterium has virtually made the literal sense, "become nothing at all, for the Pope hath taken it clean away and made it his possession." This seeming acerbic polemic is not to be dismissed by a waving of the hands. He states the concrete situation by describing how the literal sense of Scripture is taken away by the Pope, one, by the "counterfeited keys of his traditions, ceremonies, and reigned lies," and two, "partly driveth men from it with violence of sword, for no man dare abide by the literal sense of the text, but under a protestation, 'if it shall please the Pope.' " Fast forward to the present day. Those past circumstances don't hold true today, but there is a discernible difference today between some within the evangelical academy, let's say, and a regular member of a confessional Protestant local church. If you've ever been told or taught that a believer cannot, that is, it is impossible to interpret the Scripture apart from the history of the church's interpretation of it, does this not militate against the perspicuity of Scripture? Or worse, perhaps it militates against Sola Scriptura itself. Instead of the phrase, if it shall please the Pope, we may hear, for all practical intents and purposes, if it shall please the Church Fathers or if thus saith church history. This whole matter is not one of consultative desirability and permissiveness in biblical interpretation, but its indispensability and necessity for the interpreter to access those consultative sources as if they were more understandable or authoritative that Scripture. The confessionally Reformed answer must continue to be both the analogy of Scripture and the analogy of faith for the Academy, the Pulpit, and the Pew. Tyndale continues with the quadriga's three further senses. He states that the Tropological and Anagogical are simply superfluous since they accomplish what the allegorical sense seeks to do. "Tropological and Anagogical are terms of their own feigning, and altogether unnecessary, for they are but allegories, both of them. And this word comprehended them both and is enough. For Tropological is but an allegory of manners, and Anagogical an allegory of hope." For Tyndale and his hermeneutical heirs, the Tropological and Anagogical interpretation amounts to taking Scriptural speech and finding an analogy and expressing it with borrowed speech. There is a source and there is a target. Tyndale says, "An allegory is as much to say as strange speaking or borrowed speech as when we say of a wanton child, 'This sheep hath maggots in his tail. He must be anointed with birch and salve,' which speech I borrow of the shepherds." So, we can see by this illustration that Tropological meaning in this speech borrowed from shepherds is the literal sense of the allegorical expression. But this is true by rightly understanding the literality or literalness of the words themselves. Tyndale anticipates William Whitaker by adducing that this consideration hints at the sense of Scripture being single, and namely, the literal. Tyndale is consummately rational in maintaining, "That the Scripture hath but one sense, which is the literal sense. And that literal sense is the root and ground of all, and the anchor that never faileth, whereunto if thou cleave, thou canst never err or go out of the way." I've heard many seminary profs and pastors online and through podcasts echo something deceptively similar, but not quite. They say, the quadriga is legitimate as long as we collapse the three non-literal senses into the literal sense. This collapse can only mean, however, that the sense of Scripture is both one and literal. The medieval quadriga was advocating for the fourfold sense, not collapsing the spiritual senses into the single literal sense. The reason the Reformers and some post-Reformation scholastics addressed the issue was not to rehabilitate or retrieve the quadriga, but to clarify and advocate for the single literal sense of Scripture as the correct position. It escapes some of these Protestant, Evangelical, and Reformed men that t he quadriga's legitimacy stands or falls on whether the sense of Scripture is manifold or one. It does absolutely no good to the cause of rehabilitating or retrieving the historical quadriga for Protestants or Evangelicals to acknowledge in Scripture its compositional affordances, its communicative ornaments, its figurative language, and its artistic license to do with words what its human authors or its divine Author saw fit. Tyndale lists "proverbs, similitudes, riddles, allegories, as all other speeches do. But that which the proverb, similitude, riddle, or allegory signifyeth is ever the literal sense which thou must seek out diligently." Tyndale goes on to mention common English idiomatic expressions full of rich borrowed speech from one thing and applied to another thing to create something new. These features of Biblical content and style, known to both Catholics and Reformers, don't bridge the great gulf fixed between their respective disparate conceptions of the manifold or single sense of Scripture. Tyndale continues to deny the quadriga and quadrigans' quarter if we try to conceptualize it as applications of meaning. When we draw out "the literal sense of the Scripture by the process of the text or by a like text of another place, then go we, and as the Scripture borroweth similitudes of worldly things, even so we again borrow similitudes or allegories of the Scripture, and apply them to our purposes, which allegories are no sense of Scripture, but free things beside the Scripture and all together in the liberty of the Spirit." So, then, any attempts to get preachers, for example, to embrace the legitimacy of the quadriga as a model for homiletical application are truly less than helpful or even legitimate. Tyndale is nothing but a Debbie Downer for the overly intellectually hospitable seminary profs and their up-and-coming seminarian whippersnapper acolytes, who write and appear on the podcast circuit discussing the virtues of the quadriga for sermon applications. It truly boggles the confessional mind to hear shepherds of souls express something along the lines of, "Preachers may deny the quadriga's categories in hermeneutics, but embrace them in homiletics." You may have read or listened to some seminary profs who should know better claim that if you apply the text of Scripture tropologically or anagogically, that's tantamount to the quadriga's approach. On an episode of the Preaching and Preachers Podcast, for example, Dr. Mitchell Chase was asked about the quadriga given his book on typology and allegory. Contra Tyndale and the WCF/2LBCF 1.9, he stated, "I would love to see a resurgence of appreciation for it among preachers." Tyndale, however, was consistent in rejecting the Quadriga in Hermeneutics and homiletics. He stated : "...take an ensample. Thou hast the story of Peter, how he smote off Malchus's ear, and how Christ healed it again. There hast thou in the plain text great learning, great fruit, and great edifying, which I shall pass over because of tediousness. Then I come, when I preach of the law and of the gospel, and borrow this ensample to express the nature of the law and of the gospel, and to paint it unto thee before thine eyes. And Peter and his sword make I the law, and of Christ the gospel, saying, 'As Peter's sword cutteth off the ear, so doth the law, the law dammeth. The law killeth and mangleth the conscience. There is no ear so righteous that can abide the hearing of the law. There is no deed so good that the law dammeth. But Christ, that is to say, the gospel, the promises and testament that God hath made in Christ, healeth the ear and conscience, which the law hath hurt. The gospel is life, mercy and forgiveness, freely and altogether and healing plaister. And as Peter doth hurt and make a wound, where was none before, even so doth the law. For when we think we are holy and righteous and full of good deeds, if the law be preached aright, our righteousness and good deeds vanish away as smoke in the wind, and we are left damnable sinners only. And as thou seest how Christ healeth not, till Peter hath wounded, and as a healing plaister helpeth not, till the corrosive hath troubled the wound, even so, the gospel helpeth not, but when the law hath wounded the conscience, and brought the sinner into the knowledge of his sin.' " What is Tyndale's point? After waxing eloquent in this hypothetical homiletical display of rhetorical prowess, he states, "This allegory proveth nothing. Neither can do, for it is not the Scripture, but an ensample or a similitude borrowed of the Scripture to declare a text or a conclusion of the Scripture more expressly, and to root it and grave it in the heart. For a similitude or an ensample doth print a thing much deeper in the wits of a man than doth a plain speaking, and liveth behind him, as it were, a sting to prick him forward, and to awake him withal." Does this sound like a sense of Scripture or a communication strategy and tool? Talk about the wrong meaning from the right text. This is the result of recommending the quadriga's manifold sense of Scripture for preaching. It conflates meaning with application and gets both wrong. Putting a spotlight on an intended rhetorical flourish for a homiletical outcome should not be conflated with a sense of Scripture. Tyndale's point, using the law gospel illustration, with borrowed speech from the story of Peter smiting Malchus' ear, is that despite the seemingly pragmatic ease with which allegorizing the text to say something good, but different, and other than what the text actually says, such a strategy, "proveth nothing, neither can do, for it is not Scripture, but an ensample or similitude borrowed of the Scripture..." To use a term from the art of rhetoric-- invention --that is, the process of deriving and formulating by the mind of the rhetorician, or in this case, the preacher, is what borrowed speech really is--not a spiritualized or allegorical sense or application. But the preacher must distinguish between a compositional allegory and an interpretive allegory. The former may be a feature of Biblical literature here or there (few genuine examples exist), not one of the four senses of Scripture itself. The latter is more akin to the quadriga's imposed external to Holy Writ spiritualized domain of meaning. There is much food for thought in Tyndale's reasoning for the teaching aspect of preaching the word. Unfortunately for those trying to rehabilitate or retrieve the quadriga for Protestant appreciation and use, there is no rational or logical quarter for relying on the quadriga as a resource to help one charged with deriving meaning from Scripture to then proclaim that meaning. Tyndale continues, "Moreover, if I could not prove with an open text that which the allegory doth express," that is the law/gospel illustration, "then were the allegory a thing to be jested at , and of no greater value than a tale of Robinhood ." Now, let me give a contemporary example of such an allegory worthy to be jested at. In his book, titled Manual for Preaching, medical doctor, seminary professor, and preacher, Abraham Kuruvilla, details an experience he had while waiting in the foyer of a church he was visiting. He says, "I found a copy of a popular daily devotional that I spotted a homily on Acts 28. Paul is shipwrecked on Malta, and he joins everyone else in helping out, picking up sticks for the fire. So the writer recommended we too should be willing to do menial jobs in churches and always be willing to do even the lowliest job. Of course, the devotional conveniently failed to mention the viper that came out of the cord and bit the hapless apostle. Now I, being the clever guy that I am, could use that part of Acts 28 to recommend exactly the opposite. Never ever do menial tasks, because who knows? A venomous beast, usually of the two-legged variety, may sink its fangs into you.” Kuruvilla's anecdote, several centuries removed, seems to encapsulate and confirm Tyndale's various conclusions. In this example, the tropological sense is nothing but an allegory of manners. Be willing to do menial work based on Paul doing menial work. With text-based mischief, Kuruvilla also illustrates that a contradictory tropological allegory of manners can equally be commended, hence the jest, as Tyndale said. Indeed, the quadriga's ultimate value for both hermeneutics and homiletics is as a thing to be jested at Biblically, rationally, historically, and confessionally. Whether conceived as manifold sense or manifold application, the Protestant rejection of the quadriga was not due to its abuses, but to its inherent defects. The principle of the manifold sense of Scripture cannot be resolved much less incorporated into a confessionally Protestant single sense of meaning model by an appeal to semantics. The principles themselves are opposed. From its attempted sophisticated rehabilitation or retrieval under the guise of Christocentrism or interpreting the Scriptures like the Apostles to its painfully superficial means of conceiving it as an applicational tool for preaching, the quadriga's true forte is in its propensity to inspire jest. J.R.R. Tolkien's famous quadriga easter egg is a classic example: “Good Morning!” said Bilbo, and he meant it. . . . “What do you mean?” he said. “Do you wish me a good morning, or mean that it is a good morning whether I want it or not; or that you feel good this morning; or that it is a morning to be good on?” “All of them at once,” said Bilbo. J. R. R. Tolkien, The Hobbit (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1966), 17–18. The End!!!!